Today, while looking into visa application formalities for my parents from Canada, I came across an interesting question:

“What is the applicant’s father’s date of birth?”

I read it twice in disbelief, thinking—we live in two different worlds.

The applicant’s father’s name—my grandfather’s date of birth? Seriously? Lol. Even he didn’t know that.

I asked my dad, and he stumbled. Even a meticulous record-keeper like him found the question absurd. Many in my grandparents’ generation never received birth registration certificates in India. Birth certificates have only been issued there since 1969, when the Registration of Births and Deaths (RBD) Act made birth registration compulsory. My grandfather was born long before that.

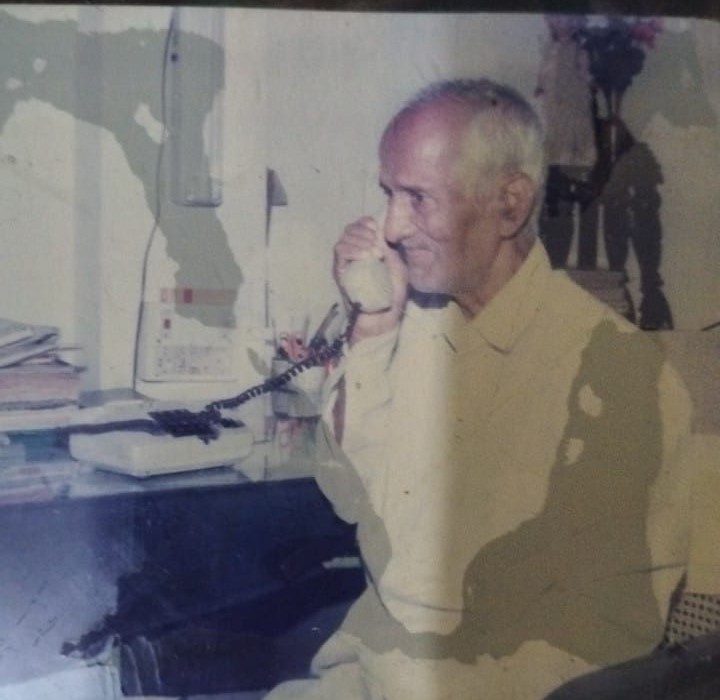

With little formal education but exceptional proficiency, he worked as an electrician in the railway department under British rule. Influenced by Gandhi yet impressed by British professionalism, he never left home in unironed clothes or unpolished shoes. A passionate traveler, he always carried a small bag containing a diary where he meticulously recorded even the smallest events—expenses made, receipts collected and the newspaper clippings which had his pictures in them. His bag always had a pen, and he made sure my homework pencil was always sharpened.

But despite his sharp mind, fascination with perfection, and love for record-keeping, he never went to school and couldn’t read or write. He always found someone to do that for him—and in India, it was relatively easy to ask for help.

Evening tea time was his favorite, when we all gathered around my mother, listening to his stories about life in Sawantwadi, a coastal village near Goa, in India. He would boast flamboyantly about the extent of his relationships and the people he knew, often reminding us of his brothers, sisters, and cousins’ names and their importance in his life. But what made him truly unforgettable was his humor—and that ever-present smile that never faded.

Reading the same letters again and again was nothing new to me, but somehow, this shocking note had escaped my attention before. I started reading with conviction, and after a few lines, I stopped, thinking the words might sound unappealing to him—almost forgetting that this must have been the hundredth time he had asked someone to read it out. Regardless, I hesitated and said,

“Let it be, Dada (Grandpa).”

But he insisted,

“No, read it.”

So I started again. It was in Marathi:

“Shaletoon satat gairhazar aslyamule kadhoon taknyat yet ahet.”

Which translates to: “Being suspended from school for consistently remaining absent.”

—His school report card.

My grandfather frowned upon hearing the words—even though he must have heard them at least fifty times before.

“What did they say? Oh, it’s so easy for them to judge, as if they ever had to toil in their chacha’s (uncle’s) field all day!” he grumbled.

“Read it again,” he ordered.

This time, I read it loudly—on purpose. He repeated his frustration, then, moments later, broke into a boyish smile. The Pathan was back in his element, and I was relieved.

But I still wonder—why would someone keep a letter like that in his bag and flaunt it like a badge of honor?

In true Pathan style, he unknowingly taught me that failures are meant to be cherished—and laughed at in time.

I hope I carry my failures with the same pride you did, Grandpa!

What an emotional write up with a hard hitting message in such less words!

Mind blowing

Very nice mention about your Grand pa’s innocent life.